An interview with JuDr. René Vašek, the Director of labor office in Jablunkov, about the situation of high unemployment in our region

Why do you think there is such a high percentage of unemployment in our region?

-High unemployment in our region is mostly caused by some historical factors. Moravian-Silesian Region used to be a strongly industrial part of our country specializing in heavy industry, for example coal mining or steel production. After the revolution in 1989 there was a change in production due to a decrease in demand which led to the closure of these companies and making many people jobless.

These employees were narrowly specialized and employed in mostly labourer-like professions. They were very often poorly educated and this led to not catching up at the labor market. Many young and educated people also left the region for better jobs and what is more, for better economical and ecological conditions.

Is the situation getting better, or is it still the same?

-Well, it really has gotten better in the past few years, but the unemployment is still one of the highest in the Czech Republic.

How long might it take to get rid of this problem?

-It is not expected to get solved immediately. It is a long-term and complicated process which relies on pushing students in the right direction that they will have guaranteed to have a job currently being in demand in the first place. For example more motivational speeches in schools are a good way to start.

In conclusion, what is your personal view on this whole situation?

-We need to perceive that even though the unemployment in this region is nearly highest in our country, it is not a high number. Historically, the percentage is the lowest it has ever been and the unemployment in the Czech Republic is the lowest in the whole EU, which is really great.

Valentina Vašková, Czech Team

Unemployment can have an impact not just on the economic well-being of a country (unused potential labour input and higher social protection payments) but also on the well-being of individuals who are without work and their families. The personal and social costs of unemployment are varied and include a higher risk of poverty, debt or homelessness, while the stigma of being unemployed can cause a reduction in self-esteem, a breakdown in family/personal relations, or social exclusion. One of the 20 underlying principles of the European pillar of social rights states that ‘the unemployed have the right to adequate activation support from public employment services to (re)integrate in the labour market and adequate unemployment benefits of reasonable duration’, as well as ‘the right to personalised, continuous and consistent support. The long-term unemployed have the right to an in-depth individual assessment at the latest at 18 months of unemployment’.

In 2018, there were 16.9 million unemployed persons aged 15-74 years in the EU-28, equivalent to 6.9 % of the total labour force. Having peaked at 26.1 million unemployed persons or 10.9 % of the labour force in 2013, the number of people without work fell overall by more than one third, or 9.2 million, with five consecutive annual reductions through to 2018. As a result, the EU-28 unemployment rate fell to a level that in 2018 was, for the first time, below that recorded at the onset of the global financial and economic crisis in 2008 (7.0 %).

The lowest regional unemployment rate was recorded in the Czech capital city region of Praha, at 1.3 %

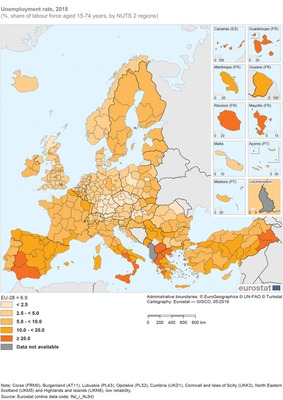

In 2018, the lowest regional unemployment rates — among NUTS level 2 regions — were concentrated together in a cluster of regions that started in western Austria, moved up through southern Germany and across into Czechia; the unemployment rate was also lower than 2.5 % in three Hungarian regions, two regions from each of Poland and the United Kingdom and one Romanian region (as shown by the lightest shade in Map 5). In 2018, Praha — the capital city region of Czechia — recorded the lowest regional unemployment rate in the EU, repeating the situation of a year before.

By contrast, the highest unemployment rates were recorded in southern and outermost regions of the EU. There were 16 regions across the EU where the unemployment rate was above 20 % in 2018, including: five regions from Greece and from Spain; three outermost regions of France, including the highest regional unemployment rate in the EU that was recorded in Mayotte (35.1 %); three regions in southern Italy. In four northern and western EU Member States — Belgium, Denmark, Germany and Austria — the highest regional unemployment rate in 2018 was recorded in the capital city region.

The EU-28 youth unemployment rate was 15.2 %

One labour market area of particular interest to policymakers is that of youth unemployment. The performance of youth labour markets is closely linked to education and training systems and reflects, at least to some degree, a mismatch between the skills obtained by young people and the skills that are required by employers (to fill job vacancies). Several EU Member States have enacted new employment laws with the goal of liberalising labour markets, for example, by providing a wider range of possibilities for hiring staff through temporary, fixed-term or zero hours contracts. In some countries this has resulted in a clear division between people with a permanent, full-time post and those with more precarious employment; the latter are often young people and/or people with relatively low levels of educational attainment.

One of the 20 underlying principles of the European pillar of social rights is that ‘young people have the right to continued education, apprenticeship, traineeship or a job offer of good standing within four months of becoming unemployed or leaving education’. In 2018, the EU-28 youth unemployment rate was 15.2 %, which was 2.2 times as high as the overall unemployment rate (among people aged 15-74 years) which stood at 6.9 %.

The information presented for regional youth unemployment often duplicates the patterns observed for the total unemployment rate, although youth unemployment rates were consistently higher for all NUTS level 2 regions, this was most notably the case in:

- three Romanian regions, where the youth unemployment rate was 4.8-6.6 times as high as the total unemployment rate — Nord-Vest, Bucuresti - Ilfov (2017 data) and Centru;

- the capital city regions of Praha (Czechia; 4.3 times as high) and Outer London — West and North West (the United Kingdom; 4.2 times as high).

Figure 2 shows that there were some considerable inter-regional variations in youth unemployment rates in 2018: this was particularly the case in France and the three southern EU Member States of Italy, Spain and Greece, where the range between the highest and lowest regional youth unemployment rates was at least 37.5 pp. The biggest difference was recorded in France, where the region with the highest youth unemployment rate was Mayotte (61.1 %) and the region with the lowest rate was Limousin (12.2 %); as such, the youth unemployment rate in Mayotte was five times as high as that in Limousin, a ratio that was only surpassed in Italy, where the region with the highest youth unemployment rate was Campania (53.6 %), some 5.8 times as high as the rate recorded for Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano/Bozen (9.2 %).

In four western EU Member States, the capital city region had the highest regional youth unemployment rate on the national territory; note, this had also been the case for the overall unemployment rate concerning Belgium, Germany and Austria — the final region was Outer London — West and North West in the United Kingdom.

Long-term unemployment share in the EU-28 was 43.2 %

This final section provides an analysis of long-term unemployment, defined here as persons aged 15-74 years who had been without work for at least 12 months. Long-term unemployment may have a considerable impact on an individual’s well-being, leading to self-doubt, anxiety or depression, while people in this situation also have a far higher risk of falling into poverty or social exclusion. Furthermore, the longer somebody remains unemployed, the less attractive they are likely to be for potential employers. One of the 20 underlying principles of the European pillar of social rights is that ‘the long-term unemployed have the right to an in-depth individual assessment at the latest at 18 months of unemployment’.

The long-term unemployment share is defined as the share of the long-term unemployed in total unemployment. In 2018, the EU-28 long-term unemployment share was 43.2 %, in other words, more than two fifths of all unemployed people in the EU had been without work for at least a year. Figure 3 shows the highest long-term unemployment share was recorded in Mayotte (81.8 %), followed by Ipeiros in Greece (77.2 %), Severozapaden in Bulgaria (76.8 %); two additional mainland regions from Greece followed — Attiki (76.0 %) and Sterea Ellada (74.3 %). By contrast, the lowest long-term unemployment shares were concentrated in Sweden and the south of the United Kingdom.