Dear students,

Your new task is to work in teams in order to present a regional/certified product of each country:

- making a blog entry about it and

- preparing a dish that contains this product.

Then we'll chat about the food product.

S O P A R N I K

Another traditional Croatian dish has been given EU geographical protection status …

Poljički soparnik (Poljički zeljanik/Poljički uljenik) has been protected and issued with the EU geographical origin label. It was registered a Protected Geographical Indication (GPI) .

Poljički soparnik is savoury pie made of finely ground wheat flour with a filling of Swiss chard. Its origins, centuries ago, are from modern-day Omiš and the surrounding areas which was once part of the Poljica Republic in the late Middle Ages and the early modern period in central Dalmatia. The original season for the dish was the colder time of the year when older, sweeter chard was available.

The soparnik is said to be the prototype of the Italian pizza, which the Romans brought to Italy. Today it is used as a cultural trademark and sold increasingly on markets and in restaurants and found on events and festivals.

Soparnik has already been declared an intangible cultural heritage of Croatia by the Croatian ministry of culture, and now it awaits protection at the European level.

Soparnik is an old Croatian food, from the area of Omiš. The dough is made from finely ground wheat flour, water and salt. You need three kilos of Swiss chard and one red onion. Spices are olive oil, garlic and salt and needs 10 minutes to bake in a komin. The komin needs to be heated for an hour. When it is done you spread olive oil and garlic on top and cut into rhomboid slices.

Receiving the status is important as it will mean accessing EU funds will become a lot easier when presenting the Poljički soparnik at fairs in Europe. Poljički soparnik is now the 10th Croatian food product protected at EU level, joining pršut from Drniš, Krk, Istria and Dalmatia, extra virgin olive oil from Cres, mandarins from Neretva, sour cabbage from Ogulin, kulen from Baranja, and potatoes from Lika.

The original season for the dish was the colder time of the year when older, sweeter chard was available.

Ingredients

Flour – 500 g

Olive oil – 3 tablespoons

Water – 250 ml

Parsley – 1 bunch

Swiss chard (blitva) – 1 kg

Spring onion – 1

Garlic – 4 cloves

Salt

Instructions

1. Wash the chard (blitva) cut out the storks. Cut into strips and place in a bowl. Finely chop the spring onion and parsley and add to the chard. Add salt and sprinkle with olive oil.

2. Time to do the pastry – in a bowl sieve the flour. Add salt, 3 tablespoons of olive oil, and water then with a mixer mix together (adding water when needed to keep moist) until it binds.

3. Sprinkle flour on a baking tray and put the (circle) shaped pastry on it. Add the chard/spring onion and parsley mixture on. Cover with the other half of the pastry which has been also rolled into a circle shape.

4. Tuck in the edges so it is all closed around.

5. Place in the oven at 200°C for around 20 minutes.

6. Crush garlic into some olive oil and paste the top of the cooked Soparnik.

Foie Gras

The Foie Gras history. (Adapted from Foie Gras Gourmet)

Since first discovered by the Ancient Egyptians over 4,500 years ago, foie gras has become a renowned delicacy right across the world:

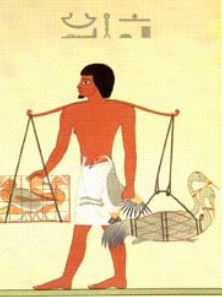

The story of foie gras begins with the Pharaohs

Ducks and geese flew over the banks of the Nile as they migrated each year. The Egyptians noticed that the geese gorged while on the fertile banks to build the energy they needed to continue their flight in safety.

So impressed by the wonderful flavour of the liver from these geese, the Ancient Egyptians began to replicate this natural feeding process.

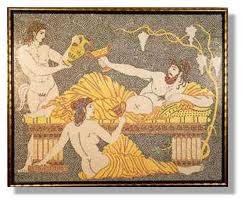

Foie gras then became a favourite dish at banquets in Ancient Greece and in the Roman Empire

After the Ancient Egyptians, the Greeks and Romans carried on the practice of fattening ducks and geese and foie gras became a central part of their feasts. Across Roman Empire, including of course Gaul, people became experts in preparing this delicacy.

In Gaul particularly, foie gras very quickly began to grace the tables of kings and noblemen who appreciated its fine and subtle flavour.

Foie gras since the 18th Century

Corn began to be introduced to South-West France in the 1700s. This, together with the discovery of a means to sterilise and preserve food meant that foie gras was able to become available across the world.

With its fine and delicate flavour, foie gras quickly became synonym of French gastronomy, representing the very best of France’s culture and heritage.

Today, it is rare to find a reputable French restaurant on whose menu foie gras does not appear.

Foie Gras controversy and Foie Gras in Europe (Adapted from Wikipedia)

The production of Foie Gras (the liver of a duck or a goose that has been specially fattened) involves the controversial force-feeding of birds with more food than they would eat in the wild.

Animal rights and welfare activist groups contend that foie gras production methods, and force feeding in particular, consist of cruel and inhumane treatment of animals.

Foie-gras production is banned in several countries, including most of the Austrian provinces, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, Turkey and the UK.

The force feeding of animals for non-medical purposes, essential to current foie gras production practices, is explicitly prohibited by specific laws in Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway, Poland, or following interpretation of general animal protection laws in Ireland, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

Since 1997, the number of European countries producing foie gras has halved. Only five countries still produce foie gras: Belgium, Romania, Spain, France and Hungary.

In France, the fattening is achieved through "gavage" (force-feeding) corn, according to French law. French law states that "Foie gras belongs to the protected cultural and gastronomical heritage of France."

As a starter, we propose SALADE GASCONNE (which includes a slice of Foie Gras). Here is the recipe in Spanish.

For the main dish, we propose MAGRET GRILLÉ SAUCE ROQUEFORT, POMMES DE TERRE SAUTÉES. Here is the recipe in ENGLISH. The magret is the duck breast of the same animal raised to produce the Foie Gras. The taste is unique and has no comparison to a regular duck breast.

Feta

Everything's betta with a little Feta

Award-winning Greek cheeses, with their unique taste, explain why in Greece the annual per capita consumption is higher than in any other European country. Soft, creamy and hard, white and yellow, fresh and mature, salty and sweet, each one a nobility, all produced with mastery and skill.

Nothing conjures up the dreamy images of Greece better than the Aegean, home to countless islands big and small and to cooking traditions as old as Homer. Islanders have their unique existence, defined by the deepest bond to place and familial roots, in common with one another, regardless of whether they come from places as off-the-beaten-track as Ikaria or as cosmopolitan as Rhodes or Santorini.

We could get a true “cheesy” taste if we go on a tour in the Aegean, specifically in the Northeastern Aegean, where cheeses vary. Manoura from Sifnos is aged in wine dregs; Kalathaki from Limnos, a lovely basket-shaped, goat's milk-white brine cheese, akin to feta, takes its name from the basket (=kalathaki) that is used to produce it.

Moving further down, we meet the Dodecanese cheeses, such as Krassotyri and Sitaka. Krassotyri is a specialty of Kos. A log-shaped, ribbed wine-soaked cheese that in recent years has begun its trip off the island. These similar wine-soaked cheeses are also produced in Nyssiros and Leros. Sitaka, one of the most unusual dairy products in Greece, is a tart, creamy spread, not unlike yogurt cheese, made from slightly fermented sheep's and/or goat's milk, which has been salted slightly and reduced over low, traditionally wood-burning fire. It is a specialty of Kassos and served with a delicious local pasta dish together with caramelized onions.

In ancient Greece, the earliest records of cheesemaking can be found in Homer‘s ‘Odyssey’ where the Cyclops Polyphemus was the first to prepare feta’s ancestor. According to the myth, he used to transport the milk from his sheep in skin bags made of animal stomachs, when one day, he realized to his great surprise that the milk had curdled and taken solid form – and actually tasted good.

Feta cheese is first mentioned during Byzantine times and was called ‘prosphatos’, and associated with Crete. Pietro Casola, an Italian traveler visiting Heraklion in Crete in 1494, distinctly described the production and storage of feta in brine. But it was in the 17th century that Greeks started using the name ‘feta’ (literally meaning slice), which may refer to the practice of slicing up cheese to be stored.

Since the early 20th century, feta cheese has established itself as a major part of the Greek diet and is associated with the traditional way of life. Widely exported, feta is enjoyed abroad as it is at home – as an essential part of the Greek salad, a delicious starter available in virtually any restaurant or taverna in the country. It is also eaten with olive oil and oregano (plain or baked) or mashed with red peppers (an appetizer called “tyrokafteri”), in pies or “bougatsa”, in “kayana” and “strapatsada” (a kind of omelet with eggs, feta, tomatoes and herbs), with summer dishes (like okra, green beans, stuffed vegetables) or with melon, watermelon or grapes!

Feta occupies 70% stake in Greek cheese consumption. The cheese is protected by EU legislation and only those cheeses manufactured in Macedonia, Thrace, Thessaly, Central Mainland Greece, the Peloponnese, and Lesvos can be called ‘feta’. Similar cheeses produced elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean and around the Black Sea, outside the EU, are often called ‘white cheese’.

Feta cheese is a nutrient-rich option as it contains valuable ingredients like calcium, phosphorus, Vitamin A, Vitamin B12, sodium and proteins of high biological value. Feta is easier to digest and much less allergenic and inflammatory than cheeses made from cow’s milk, which makes it a better option for those who may be sensitive to dairy products. Feta, can be consumed by people intolerant to lactose due to its small amounts of lactose.

To create traditional feta, the goat and sheep milk is collected and placed in special ice cubes. It is transferred refrigerated to the factory where it is controlled and is passed through filters. Then it falls into pots-kettles and is heated to pasteurize or sterilize in a pasteurizer. It is cooled and then placed in special cauldrons, the coasters, where microorganisms are added. After 20 minutes the milk stirs and creates the cheese curds which are “cut” with special knives. Then a large amount of cheese whey is released from the curd and the curd is molded and lets to drain naturally. During the natural drainage and when the curd is stabilized, it is salted in its surface with coarse salt and is inserted in wooden barrels (the result is feta to be more spicy and tougher here) or metallic receptacles (here we have milder taste, smoother flavor and softer texture) to which is added salt solution. According to the law fate cheese matures for at least 2 months. Upon maturation of 2 months, feta is sold in blocks submerged in brine.

The firmness, texture, and flavor are also different from region to region, but in general, cheese from Macedonia and Thrace is mild, softer and creamier, less salty with fewer holes. Feta made in Thessaly and Central Greece has a more intense, robust flavor. Peloponnese feta is dryer in texture, full flavored and more open. Local environment, animal breeds, cultures all have an impact on the texture, flavor and aroma of feta.

photo source: http://www.feta-paraschos.gr/τυροκόμηση

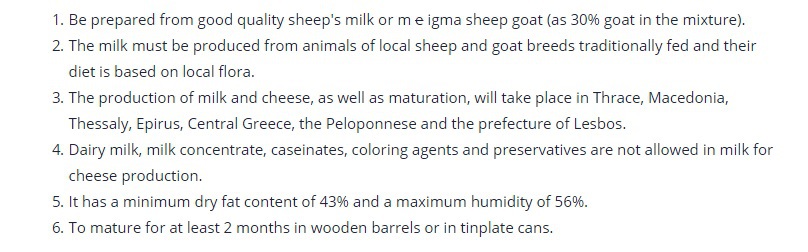

To have a white cheese the right to be called “feta” it has to follow some criteria:

Talking about cheese....what about some traditional pies with feta cheese??? Come!!! We have a contest!!!

If you don't know how to prepare traditional pies, take a look in this video we made for you during our cooking session, to see the way that our students prepared their pies!!! Before you think that we are cooking without gloves we have to tell you that our grandma doesn't wear gloves when she makes pies!!! :)

Do you cook pies? Which is your favorite one? Share with us pies from your country..

Pasztecik Szczeciński

The last weekend in Szczecin (the capital of West Pomerania) was devoted to "Pasztecik Szczeciński". We celebrated its 49th birthday. You can ask: What is it? or How can a dish have birthday? Actually, it can. And that's how it all started ...

After the war Russian troops stationed in Szczecin for a number of years. They had three machines for mass production of dumplings. In 1969 one of these machines was given to the food cooperative in Szczecin. Ms Bogumiła Polańska who was in charge of the first fast food point in Szczecin changed the forms used in the machine to shape dumplings and started producing this original treat. Those first "paszteciki" were stuffed with meat and served with clear borscht. Later, in times of crisis - also with eggs, cheese or meat minced with vegetables or sour cabbage (sauerkraut). In 2010 it was officially certified as a traditional product.

How does it taste? Of course - delicious. It's made of deep fried yeast dough with a filling. The most common filling at present are: meat, cheese with champignons or sauerkraut with mushrooms. What's important - it's really cheap - 1 pasztecik costs 3,5 PLN which is less that a Euro. You can buy it in many places in Szczecin (practically in all major shopping centres), but the original machine still works in Wojska Polskiego street near the catherdal. Supposedly these are the best. If you ever come to Szczecin, you must try it. You cannot buy it anywhere else.

Ingredients (for 10-12 pieces):

DOUGH:

½ kg flour, 250ml warm milk, 30g yeast, 1 teaspoon of sugar,

1 egg+2 egg yolks, a pinch of salt, 60g melted butter

FILLING

½ kg mushrooms, 20-30 dag cheese

Oil for frying

Suska sechlońska

Do you know why people of my region prefer suska sechlońska dried plums to the dried plums from California? Although they look similar, the taste of 'suska sechlońska' is much better because it undergoes both drying and smoking. The smoke gives the fruit a unique colour, aroma and taste.

What does the name ‘Suska sechlońska’ mean?

‘Suska sechlońska’ is a dried and smoked plum. In our regional dialect 'suska’ means dried and ‘sechlońska’ derives from the name of the village Sechna situated in Laskowa commune, Małopolska Voivodeship, from where the tradition of drying originates. The plum is grown within the administrative boundaries of four communes: Laskowa, Iwkowa, Łososina Dolna and Żegocina. Only fruits of Prunus domestica L. ssp. domestica and its varieties (Promis, Tolar, Nektawit, Valjevka and Stanley) are used for the production of ‘suska sechlońska.’ It has Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) label.

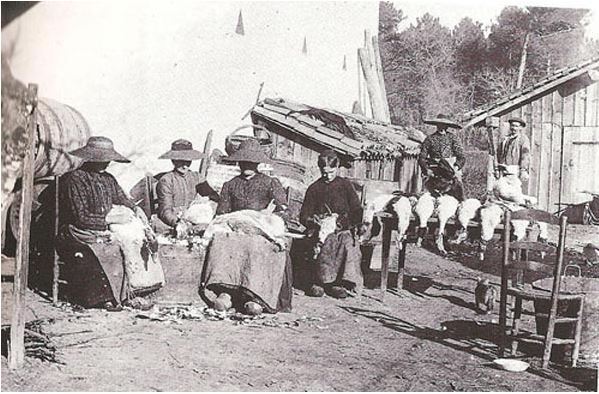

How is it produced?

Fruits are gathered when they are just NOT ready to eat raw, then they are sorted to eliminate rotten and defective ones. After that, they are laid down on a special kind of grill called ’laski’ in a layer 30 to 50 cm thick. Plums are dried in temperature ranging from 45 to 60 degrees C in specially prepared kilns, characteristic to this region. There are as many as 677 such kilns here, which is clear evidence of the product's very close link to the geographical area. The process of drying and smoking in the driers is carried out with hot smoke, which distinguishes the Suska sechlońska from traditional prunes dried with warm air. Only wood containing minimal amonut of resin is used to keep the right level of heat in the kiln.It takes about 4-6 days to finish producing one batch of 'suska’.

As the legend goes...

Drying plums in Sechna have been done for more than 300 years. As the legend goes, a local clergyman commanded local folks to plant fruit trees as the fulfilment for their sins. As people were planting trees, it turned out that pear or cherry trees were not giving a lot of crops on this terrain. The thoughtful priest suggested planting plum trees as well as drying plums so that the peasants couldn’t make alcohol from them.

How is it celebrated?The Prune Festival (Święto Suszonej Śliwki), held at Dobrociesz since 2001, features the prunes: their nutritional values and ways of using them for preparing dishes.

The Prune tourist trail indicates farms with plum orchards and drying facilities.

The prunes have been awarded and distinguished in

numerous competitions:

- distinction in the 2000 ‘Nasze Kulinarne Dziedzictwo’ competition;

- prize at the ‘Perła 2004’ competition for the best Polish regional food product;

- first prize in the 2006 ‘Małopolski Smak’ poll.

Why does the plum need public relations?

Plums are a rich source of nutrients and are a great ingredient for desserts, pastries, juices, jams as well as porridges and meat dishes. One Polish speciality is chocolate -covered prunes.

However, in Polish language there is an idiom which links the plum with a trouble. “Wpaść jak śliwka w kompot” (literally: “to fall like a plum into compote”) means “to find oneself in a difficult and awkward situation.” This is why we want to find some more positive plum related idioms in other languages. Could you help us?

Why are dried plums good for you?

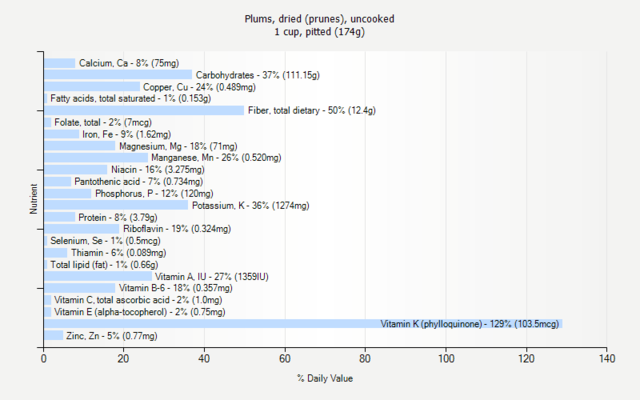

Prunes are rich in antioxidants, vitamin K, vitamin A, potassium, manganese, magnesium, copper, dietary fiber and carbohydrates. Definitely worth eating and available year round.

The author of the entry and the photo Autumn with Dumplings (below) is Beata Orzeł, the student of ZS Nr 1, class 2G. The information adapted fromOfficial Journal of the European Union 2010 / C 35/10. The graph is sourced from: http://www.weightchart.com/nutrition/info-plums-dried-prunes-uncooked.aspx.

DUMPLINGS WITH SUSKA SECHLOŃSKA PRUNES

LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW

Let us know how you like to eat prunes: alone as a snack or with other dishes. Is there a phrase/an idiom about the plum in your language?Share your thoughts with us.

To leave your comments, click Join the chat button and follow the instruction.PLEASE, WRITE YOUR TRUE NAME.