To Zakynthos (English translation)

"Never will I touch your sacred shore again

where my young form reclined at rest,

Zakynthos, regarding yourself in waves

of the Greek sea, where Venus was

virgin born, and made those islands bloom

with her first smile; nor did he bypass

your lacy clouds and leafy fronds

in glorious verse, the one who sang

of fatal seas, and of the broad exile

after which, exalted by fame and by adventure,

Ulysses kissed his rocky native Ithaca.

You will have nothing of your son but his song,

motherland of mine: and our fate already

written, the unmourned grave."

This is a famous sonnet written by an Italian poet, Ugo Foscolo, in 1803.

It belongs to the Pre-Romantic period, in which poets explained their feelings, always disappointing towards the historical present: they tried to find a haven where to have a rest and where to escape from a negative world.

Very often this literate movement resulted in a rediscover of the classical values, such as the faith, the armony and the balance in order to obtain a life without any doubts or preoccupations, like in the Epicurean philosophy.

This sonnet opens with a negation: “Never” implies that Foscolo wouldn’t have returned to his homeland and he seems almost depressed for this fact ( the Italian version is even more remarkable since it opens with a triple-negation that makes the lector even more aware of Foscolo’s condition).

The third line starts with an invocation to Zakynthos and the poet tries to give his land a celestial value saying that the sea that flows through it, is the metaphorical womb of Venus, the goddess of love, one of the most important virtues of Romanticism.

In this meaning Zakynthos becomes the homeland of harmony and for the poet it becomes a sort of secure refuge, but it is only a form of unreachable utopia.

Then he introduces the figure of Homer and here it is distinct his intention to compare himself to Homer but also to Ulysses: in fact Foscolo is not only the poet who tells the situation of a man who has lost his homeland but also the person who lives this situation.

There are two other observations:

1)the Greek Sea is rich in poetic sensitivity in fact the Homeland of Ulysses finds itself in the this sea;

2)on the contrary of Ulysses that has come back home, Foscolo couldn’t do it: the fate has divided him from Zakynthos.

Foscolo is also really sorry for having a “unmourned grave” since none of his relatives would have visited his tomb.

I have chosen this poem because it is very touching and it is well-fitting with the situation of immigrants in our society: in the majority of cases, they leave their birthplace with the awareness that they won’t return there, so they won’t see their relatives or their friends more.

Also the fact that you don’t have your tomb in your mother land is very sad: in fact your loved ones hardly ever will go to your new country in order to visit your deceased body.

So, let’s reflect how an immigrant feels in a new country and try to integrate them in the best way possible…by the way, this is an Italian poem, so how about publishing a poem of your mother tongue language (always translated) pertinent to the immigration and analysing it? This could be a good idea!

The house near the sea - Seferis Giorgos

The houses I had they took away from me. The times

happened to be unpropitious: war, destruction, exile;

sometimes the hunter hits the migratory birds,

sometimes he doesn’t hit them. Hunting

was good in my time, many felt the pellet;

the rest circle aimlessly or go mad in the shelters.

Don’t talk to me about the nightingale or the lark

or the little wagtail

inscribing figures with his tail in the light;

I don’t know much about houses

I know they have their own nature, nothing else.

New at first, like babies

who play in gardens with the tassels of the sun,

they embroider coloured shutters and shining doors

over the day.

When the architect’s finished, they change,

they frown or smile or even grow resentful

with those who stayed behind, with those who went away

with others who’d come back if they could

or others who disappeared, now that the world’s become an endless hotel.

I don’t know much about houses,

I remember their joy and their sorrow

sometimes, when I stop to think; again

sometimes, near the sea, in naked rooms

with a single iron bed and nothing of my own,

watching the evening spider, I imagine

that someone is getting ready to come, that they dress him up

in white and black robes, with many-coloured jewels,

and around him venerable ladies,

grey hair and dark lace shawls, talk softly,

that he is getting ready to come and say goodbye to me;

or that a woman — eyelashes quivering, slim-waisted,

returning from southern ports,

Smyrna Rhodes Syracuse Alexandria,

from cities closed like hot shutters,

with perfume of golden fruit and herbs —

climbs the stairs without seeing

those who’ve fallen asleep under the stairs.

Houses, you know, grow resentful easily when you strip them bare.

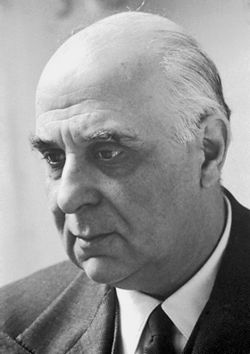

About Giorgos Seferis

His original surname was Georgios Seferiades. He was and is one the leading lights of the Greek poetry, the first Greek Nobel laureate

for literature (1963), essayist and diplomat. He was born on 13 March 1900 in Smyrna and died on 20 September 1971 in Athens.

He is the most distinguished Greek poet of 'the generation of the '30s', which introduced symbolism to modern Greek literature. His work is permeated by a deep feeling for the tragic predicament of the Greek, as indeed, of modern man in general.