Newspaper articles for April 2020 from IES MAESTRE DE CALATRAVA, Ciudad Real

Insatiable

Netflix launched this TV series, Insatiable, in 2018. Two seasons have been released for the moment, and the third is coming soon (though rumors say it would be cancelled). Insatiable is at the same time a black comedy, a romantic series and a teenagers’ story. Before its premiere, some people refused to broadcast it due to the kind of message being conveyed and its possible interpretations.

Insatiable is about Patty, a chocolate-loving teenager that has gone through harassment her whole life. One night at a shop she is attacked and robbed a chocolate bar. The impact of that event makes her spend the summer only on liquids. When coming back to high school in September she has dramatically changed and slimmed down. All others are now kind and friendly to her due to her new look.

Patty signs up in beauty contests to get a revenge on those who laughed at her, thanks to Bob, a discredited lawyer who is knowledgeable in beauty contests. The plot shows how Patty intends to take revenge and also how, due to that, her relations with her best friend start to tumble.

It is also about Bob’s life since he meets Patty. Often taken as gay due to his presence in beauty contests, Bob’s marriage also starts to tumble as Patty gets in between Bob and his wife Coralee.

In my opinion, this is a good series for those who like black comedy. I deem incorrect the topic, a girl that recovers attention of boys thanks to her new slim figure. I know the series does not want to convey that message, but it is obviously the first impression. That’s why is caused refusal among criticists, as the potential offence to many people that the message may provoke. As mentioned above, the third season is possibly suspended.

Author: María José Polo Gómez del Pulgar

Original article is available in the school digital newspaper Calatravatimes

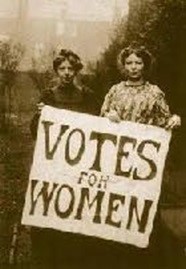

Women’s Suffrage

This political movement began during the 19th century. It sought to achieve the right of women to vote in elections. It is considered to formally start with the Declaration of Sentiments at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, and considered as ended in 1948 with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which states Women’s right to vote as a universal human right.

United Kingdom

The first milestone of the British Women’s Suffrage Movement was an action undertaken by John Stuart Mill in 1866 in the Parliament. He submitted a request signed by 1,500 women demanding to include women’s right to vote in the Suffrage reform under debate by that time. By then, only the heads of family and landowners had suffrage rights.

The refusal to this request triggered the creation of many Women’s Suffrage Societies all across the 70’s decade. These societies, linked to liberal parties, intended that the latter presented projects of law aligned with their goals. They all unified in the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies – NUWSS.

Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847-1929) was the head of the moderate suffragists that grouped within the NUWSS. This Union reached 100,000 members in 1914, and focused on political propaganda, by arranging demonstration and persuasion campaigns but always keeping a line of law and order.

Millicent Garrett Fawcett (1847-1929) was the head of the moderate suffragists that grouped within the NUWSS. This Union reached 100,000 members in 1914, and focused on political propaganda, by arranging demonstration and persuasion campaigns but always keeping a line of law and order.

As this moderate strategy did not produce outcomes, Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) created the Women’ Social and Political Union. Its members were eventually known as the “Suffragettes”. While the Parliament debated about the legal reforms allowing the women’s vote, the WSPU, in addition to traditional propaganda means as meetings and demonstrations, triggered violent actions like sabotage, setting fire to shops and public facilities, or aggression in private homes of known politicians and MPs.

Pankhurst’s WSPU had a completely different approach from NUWSS’s. The latter intended to achieve outcomes through actions potentially accepted by the conservatory government ruling by then. The former, though, aligned with its socialist component, deemed these actions as a useless effort, as soon as the request reform was not interesting for the government, and concluded that the only way to go forward was to raise the public opinion and create interest on this topic. Consequently, calling for attention was a target to achieve at any price, thus hostile actions might eventually be useful for the cause.

Serious riots burst due to their actions and the answers of the affected, so they ended up arrested by the police. When asked to choose between a fine and the prison, they used to choose prison to collect more attention in the mass media.

Suffragettes responded to the growing governmental repression by carrying out hunger strikes in the prison, which caused brutal forced feeding as the final result.

The governmental response to this situation was really original. The Parliament approved a law known as the “Cat and Mouse” law. The mice – women – would be liberated from prison by the cat – the state - whenever their physical status became critical. However, once physically recovered, arrests and imprisonment started all over again.

Before WWI, the violence of the Women’s Suffrage protest made the political parties to reconsider their attitude towards women’s vote.

WWI set a standpoint in the Women’s Suffrage demands, and after the conflict, when women accumulated merits as the workforce that allowed the survival of economy, women’s suffrage was eventually accepted. It was February the 6th of 1918 when the British Parliament adopted the Representation of the People Act 1918, which finally accepted that eight million women, all the aged over 30, were included in the election voters’ registry. It took 10 more years to finally allow women over 21 to vote, same as men.

Spain

Women could participate in the Spanish Parliament since the Cadiz Courts in 1912. This means that the so-called “passive” suffrage started in Spain for women since the beginning of 19th century.

When the Second Spanish Republic was set in April 1931, many women struggled to be allowed to vote, as soon as the law allowed them to be voted but not to vote. It was Clara Campoamor, Radical Party’s MP, who promoted the women’s vote and legal equality with men, as well as the right to divorce, succeeded in her endeavor on October the 1st 1931 with 161 votes in favour, 121 against, and 188 abstentions.

More than 6,5 million women with the right to vote could eventually participate in the elections of November the 19th 1933, voting to their representatives, and becoming full right citizens.

Author: Carmen Alicia López Ruiz

Original article is available in the school digital newspaper Calatravatimes

List of countries and dates of women’s vote acceptance:

| COUNTRY | APPROVAL DATE |

| New Zealand | 1893 |

| Australia | 1902 |

| Finland | 1906 |

| Norway | 1913 |

| Denmark | 1915 (women over 25 who paid taxes could vote since 1908) |

| Georgia | 1918 |

| Ireland | 1918 |

| Poland | 1918 |

| Russia | 1918 |

| Germany | 1919 |

| Belgium | 1919 |

| Iceland | 1919 |

| Luxemburg | 1919 |

| Netherlands | 1919 |

| Sweden | 1919 |

| Austria | 1920 |

| Czech Republic | 1920 |

| USA | 1920 |

| Hungary | 1920 |

| United Kingdom | 1920 |

| Ecuador | 1929 |

| Spain | 1931 |

| Uruguay | 1932 (voting for first time ever in 1938) |

| Cuba | 1934 |

| Turkey | 1934 |

| Philippines | 1937 (by means of a referendum won in 1935 which scored 95% in favour) |

| El Salvador (limited) | 1939 |

| Canada | 1940 (finally in Quebec. Approved in the rest of the country from 1916 to 1922) |

| Dominican Republic | 1942 |

| France | 1944 |

| Jamaica | 1944 |

| Guatemala (limited) | 1945 |

| Italy | 1945 |

| Panama | 1945 |

| Albania | 1946 |

| Japan | 1946 |

| Trinidad & Tobago | 1946 |

| Argentina | 1947 |

| Bulgaria | 1947 |

| Venezuela | 1947 |

| Yugoslavia | 1947 |

| Belgium | 1948 (women could vote in municipal elections since 1920) |

| Rumania | 1948 |

| Surinam | 1948 |

| Chile | 1949 (women could vote in municipal elections since 1935) |

| Costa Rica | 1949 |

| Barbados | 1950 |

| Haití | 1950 |

| India | 1950 |

| Antigua & Barbuda | 1951 |

| Dominique | 1951 |

| Grenada | 1951 |

| San Vicente & Granadinas | 1951 |

| Santa Lucía | 1951 |

| Bolivia | 1952 |

| Greece | 1952 |

| San Kitts & Nevis | 1952 |

| Guyana | 1953 |

| México | 1953 (women could vote in municipal elections since 1947) |

| Pakistan | 1954 |

| Syria | 1954 |

| Ivory Coast | 1955 |

| Egypt | 1955 |

| Honduras | 1955 |

| Nicaragua | 1955 |

| Peru | 1955 |

| Vietnam | 1955 |

| Tunisia | 1956 |

| Colombia | 1957 (women could vote in the province of Velez-Santander since 1853. They lost the right to vote then the State of Santander was constituted in 1857. The right was recovered on August the 25th 1954 and became operational in 1957) |

| Brazil | 1961 |

| Paraguay | 1961 |

| Bahamas | 1962 |

| Monaco | 1962 |

| Irán | 1963 |

| Kenia | 1963 |

| Belize | 1964 |

| Portugal | 1971 (women who had completed high school could vote since 1931) |

| Switzerland | 1971 |

| Liechtenstein | 1984 |

| Central African Republic | 1986 |

| Djibouti | 1986 |

| Samoa | 1990 |