The Greek theatre

The Greek theatre history began with festivals honoring their gods. A god, Dionysus, was honored with a festival called by "City Dionysia". In Athens, during this festival, men used to perform songs to welcome Dionysus. Plays were only presented at City Dionysia festival. Athens was the main center for these theatrical traditions. Athenians spread these festivals to its numerous allies in order to promote a common identity. At the early Greek festivals, the actors, directors, and dramatists were all the same person. After some time, only three actors were allowed to perform in each play. Later few non-speaking roles were allowed to perform on-stage. Due to limited number of actors allowed on-stage, the chorus evolved into a very active part of Greek theatre. Music was often played during the chorus' delivery of its lines.

Ancient Greek theatre

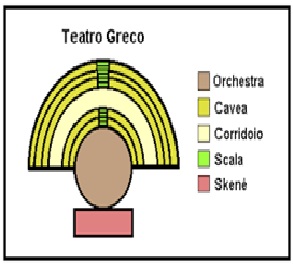

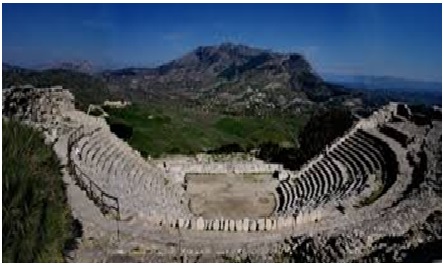

Ancient Greek theatres were very large, open-air structures that took advantage of sloping hillsides for their terraced seating. Because of drama's close connection with religion, theaters were often located in or near sanctuaries. The theater pictured here, for example, is set on the slopes of Mt. Parnassus above the famous temple of Apollo at Delphi (home of the Delphic oracle that figures so prominently in the myth of Oedipus). Similarly, the Theater of Dionysus in Athens was situated in the sacred precinct of Dionysus at the foot of the Acropolis. See also the theater on Apollo's sacred island of Delos. The theater in Epidaurus, discussed below, was near the sanctuary of Asklepios, god of healing. Many of these theaters were built in relatively open areas with lovely vistas, and the view from the Delphi theater is truly breathtaking. The core of any Greek theater is the orchestra, the “dancing place” of the chorus and the chief performance space. Almost nothing remains from the fifth-century structure of the Theater of Dionysus in Athens, but later theaters suggest that the original orchestras were full circles; see, for example, this aerial view of the theater at Epidaurus. This is the best-preserved of all extant Greek theaters; the ancient plays are still being performed here, and this computer animation will help you to recreate the experience. Although this theater was built at the end of the fourth century BCE and rebuilt and enlarged in the second century, it does enable us to visualize what the ancient theaters must have been like. The orchestra is approximately 66 feet in diameter; this photo shows the orchestra at Epidaurus with a modern set for a production of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound. An altar of Dionysus was usually located in the center of the orchestra. The audience sat in the theatron, the “seeing place,” on semi-circular terraced rows of benches (in the earliest theaters these were wooden; they were later built of stone). The Greeks often built these in a natural hollow (a koilon), though the sides were increasingly reinforced with stone, as can be seen in this overhead view of Epidaurus. Scholars often use the Latin word for hollow, cavea, to designate the seating in an ancient theater. Stairs mounting to the highest levels divide the sections of seats into wedges; at Epidaurus there are 55 semi-circular rows, providing an estimated seating capacity of 12,000-14,000. Although the name theatron suggests an emphasis on sight, in reality actors and chorus would look rather small even from seats only part-way up, and from the top rows one would see mostly colors and patterns of movement rather any details of costuming or masks. The acoustics in this theater, however, are magnificent, and words spoken very softly in the orchestra can be heard in the top rows (as long as your neighbors are quiet).

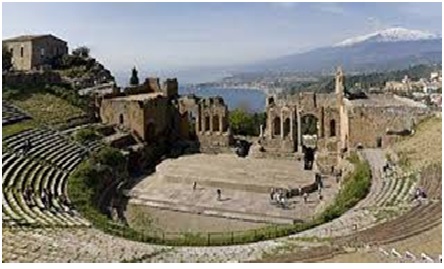

Theatre in “Magna Grecia”

Greek theatre ruins in Sicily

Segesta,

Taormina

and Siracusa

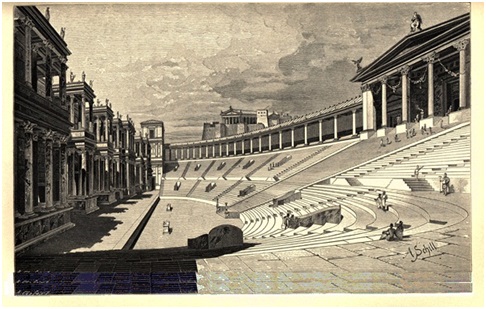

THE ROMAN THEATRE

Much of the architecture, structure, design, buildings and the plays shown in the Roman theatre were influenced by the Greek theatre. The semicircular design of the building enhanced the natural acoustics of the theatre. The entertainment available in the Roman Theatre included mime, orations, dance, choral events and different types of plays including farce, tragedy and comedy. The content of this article provides interesting history, facts and information about life in Ancient Rome including the Roman Theatre.Roman theatres derive their basic design from the Theatre of Pompey, the first permanent Roman theatre. Pompey the Great was the first who undertook the building of a fixed theatre, which was built of square stone. Roman Theatres, in the first ages of the commonwealth, were only temporary, and composed of wood.The Roman Theatre buildings were designed in the shape of a half circle and built on level ground with stadium-style seating where the audience was raised. The Roman Theatre buildings were large and could hold up to 15,000 people. The theatre itself was divided into the stage (orchestra) and the seating section (auditorium). The auditorium was occasionally constructed on a small hill or slope in which stacked seating could be easily made mimicking the tradition of the Greek Theatres. Organizing the entrances to the Roman Theatre was important in order to safely handle the number of Romans in attendance. According to Vitruvius, "The entrances (aditus) should be numerous and spacious; those above ought to be unconnected with those below, in a continued line wherever they are, and without turnings; so that when the people are dismissed from the shows, they may not press on one another, but have separate outlets free from obstruction in all parts." The surrounding Roman corridor (praecinctio) separated the galleries of a theatre were used for the walkways, concentric with the rows of seats, between the upper and lower seating tiers in a Roman theatre. The Roman theatre did not have a roof instead; an awning was pulled over the audience to protect them from the sun or rain. Another innovation was introduced to the Roman Theatre c 78 B.C - a cooling system which was provided by air blowing over streams of water.

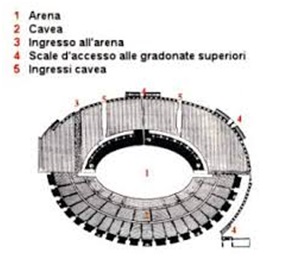

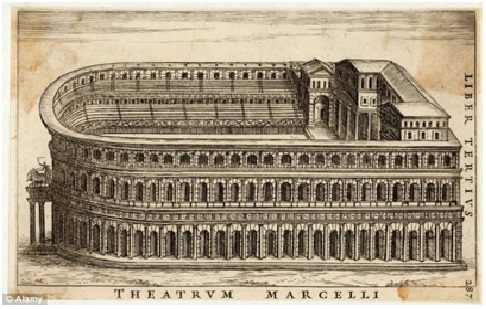

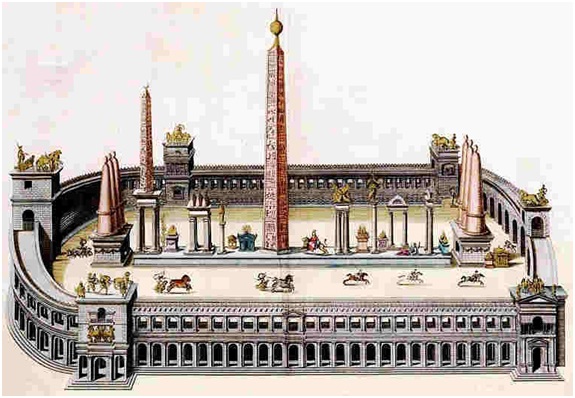

Theatre and Amphitheatre

The Roman theatres and amphitheatres were two different sorts of buildings. The Roman Theatre being built in the shape of a semicircle and the amphitheatre was generally oval. The purpose for which each type of theatre was designed was also quite different.The Roman theatres were designed for stage plays. The Amphitheatres were designed for the greater spectacles and shows of gladiators and wild animals. The Circuses (circi) such as the famous Circus Maximus which was built on a much bigger scale and designed to stage chariot races. The Naumachiae where places for the shows of sea battles. The stadia were places in the form of the circus designed for the running of men and horses. The Xysti were places constructed like porticos in which the wrestlers exercised.The Odeon was a small Roman Theatre, often roofed, used for smaller entertainment venues such as performed music poetry readings, debates, or lectures.There were, however, some similarities between the different types of Roman theatres such as the seating arrangements, styles of stage scenery and props and awnings.

In contrast to the Roman theater, which evolved from Greek models, the amphitheater had no architectural precedent in the Greek world. Likewise, the spectacles that took place in the amphitheater—gladiatorial combats andvenationes (wild beast shows)—were Italic, not Greek, in origin. The earliest secure evidence for gladiatorial contests comes from the painted decoration of a fourth-century B.C. tomb at Paestum in southern Italy. Several ancient authors record that gladiatorial combat was introduced to Rome in 264 B.C., on the occasion of munera (funeral games) in honor of an elite citizen named D. Iunius Brutus Pera. By the mid-first century B.C., gladiatorial contests were staged not only at funerals, but also at state-sponsored festivals (ludi). Throughout the imperial period, they remained an important route to popular favor for emperors and provincial leaders. In 325 A.D., Constantine (26,229), the first Christian emperor, prohibited gladiatorial combat on the grounds that it was too bloodthirsty for peacetime. Literary, epigraphic, and archaeological evidence indicates, however, that gladiatorial games continued at least until the mid-fifth century A.D. As in the case of theatrical entertainment, the earliest venues for gladiatorial games at Rome were temporary, wooden structures. As early as 218 B.C., according to Livy, gladiatorial contests were staged in the elongated, open space of the Roman Forum, with wooden stands for spectators. These temporary structures probably provided the prototype for the monumental amphitheater, a building type characterized by an elliptical seating area enclosing a flat performance space. The first securely datable, stone amphitheater is the one at Pompeii, constructed in 80-70 B.C.Like most early amphitheaters, the Pompeian example has an austere, functional appearance, with the seats partially supported on earthen embankments. The earliest stone amphitheater in Rome was constructed in 29 B.C. by T. Statilius. Taurus, one of the most trusted generals of the emperor Augustus. This building burned down during the great fire of 64 A.D. and was replaced by the Colosseum (59.570.426), dedicated by the emperor Titus in 80 A.D. and still one of Rome's most prominent landmarks. Unlike earlier amphitheaters, the Colosseum featured elaborate basement amenities, including animal cages and mechanical elevators, as well as a complex system of vaulted, concrete substructures. The facade consisted of three stories of superimposed arcades flanked by engaged columns of the Tuscan, Ionic, and Corinthian orders. Representations of the building on ancient coins indicate that colossal statues of gods and heroes stood in the upper arcades. The inclusion of Greek columnar orders and copies of Greek statues may reflect a desire to promote the amphitheater, a uniquely Roman building type, to the same level in the architectural hierarchy as the theater, with its venerable Greek precedents.

In addition to gladiatorial contests, the amphitheater provided the venue for venationes, spectacles involving the slaughter of animals by trained hunters called venatores or bestiarii. Venationes were expensive to mount and hence served to advertise the wealth and generosity of the officials who sponsored them. The inclusion of exotic species (lions, panthers, rhinoceri, elephants, etc.) also demonstrated the vast reach of Roman dominion. A third type of spectacle that took place in the amphitheater was the public execution. Condemned criminals were slain by crucifixion, cremation, or attack by wild beasts, and were sometimes forced to reenact gruesome myths.

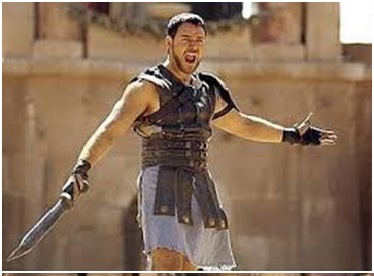

THE GLADIATORS

Adopted from the earlier Etruscans, perhaps by way of Campania, gladiatorial games (munera) originated in the rites of sacrifice due the spirits of the dead and the need to propitiate them with offerings of blood. They were introduced to Rome in 264 BC, when the sons of Junius Brutus honored their father by matching three pairs of gladiators. Traditionally, munera were the obligatory funerary offerings owed aristocratic men at their death, although the games did not have to be presented then. Elected aedile in 65 BC, Julius Caesar commemorated his father, who had died twenty years before, with a display of 320 pairs of gladiators in silvered armor (Pliny, XXXIII.53: Plutarch, V.9). Still mindful of Spartacus' rebellion, a nervous Senate limited the number of gladiators allowed in Rome (Suetonius, X.2). In 46 BC, after recent victories in Gaul and Egypt, Caesar again hosted elaborate games at the tomb of his daughter Julia, who had died in childbirth eight years earlier (together with stage plays and beast fights, they included the first appearance of a giraffe). The display was criticized, however, for its extravagance and the number slain, including several of Caesar's own soldiers, who protested that none of the money was being allotted to them (Dio, XLIII.24).During the Republic, munera had been privately financed by the family, whose duty it was to present them. Increasingly a display of aristocratic wealth and prestige, the ritual lost much of its religious significance and became more overtly political. To limit this power, Augustus assigned the games to the praetors and restricted the number of shows to two per year and sixty pairs (Dio, LIV.2.4). Eventually, the games were assumed by the emperors, themselves, as enactments of their own power. Indeed, by the end of the second century AD, Tertullian could criticize in De Spectaculis (XII) that "this class of public entertainment has passed from being a compliment to the dead to being a compliment to the living."After the slave revolt of Spartacus in 73 BC, the State assumed greater control of public games (ludi), and large numbers of gladiators were trained in imperial schools. (Interestingly, ludus means "game" and "school," because both required imitation and repetition.) Under the tutelage of a manager (lanista), a troupe (familia) of gladiators could be sold or hired out, and many were retained privately by politicians and wealthy citizens as bodyguards, especially in times of civil unrest.Most gladiators were prisoners of war, slaves bought for the purpose, or criminals sentenced to serve in the schools (damnati ad ludos). At a time when three of every five persons did not survive until their twentieth birthday, the odds of a professional gladiator being killed in any particular bout, at least during the first century AD, were perhaps one in ten. But for the criminal who was to be publicly executed (damnati ad mortem) or for Christian martyrs who refused to renounce their faith and worship the gods, there was no hope of survival in the arena.

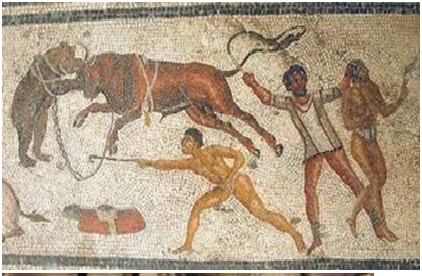

The venationes

Venationes, (Latin: “animal hunts”), in ancient Rome, type of public spectacle that featured animal hunts. Contests between beasts or between men and beasts were staged in an amphitheatre, usually in connection with gladiator shows. The men used in these exhibitions were either captives, condemned criminals, or professional animal hunters. Originating in the 2nd century bc as part of the games of the circus, such displays were immensely popular with the Roman public. Julius Caesar built the first wooden amphitheatre for the exhibition of this spectacle. The popularity of venationes became such that the world was searched for lions, bears, bulls, hippopotamuses, panthers, and crocodiles to be displayed at public celebrations and slaughtered. As many as 11,000 animals were exhibited and killed on a single occasion. Although it is uncertain how long the venationes were presented, they were still in existence after the shows of gladiators were abolished in the 5th century. Representations of venationes appear on coins, mosaics, and tombs of the period.

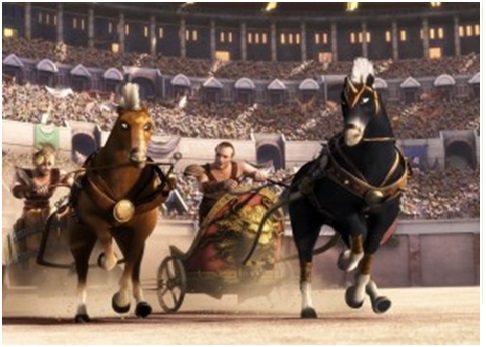

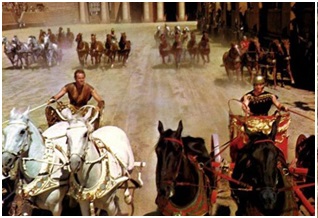

THE ROMAN CIRCUS

In addition to gladiatorial games, Romans also liked chariot-racing. Men went to the races and bet on which horses would win.The performance surface of the circus was normally surrounded by ascending seating along the length of both straight sides and around the curved end, though there were sometimes interruptions in the seating to provide access to the circus or the seating, or to provide for special viewing platforms for dignitaries and officials. One circus, that at Antinopolis (Egypt), displays a distinct gap of some 50m between the carceres and the start of the ascending seating where there is apparently no structure. This appears to be an exception.The most famous circus is Circus Maximus. In Spain a lot of Circus were built

LUDI TAURII

Ludi Taurii were games held in ancient Rome in honor of the “di inferi”, the gods of the underworld. They were not part of a regularly scheduled religious festival on the calendar. The Taurian Games were horse races, or less likely chariot races, on a course around turning posts. Festus explains that the games were performed in honor of the gods (di inferi). They were established in response to an epidemic (magna … pestilentia) afflicting pregnant women. Earlier scholars have sometimes taken the adjective taurii to mean that bulls were part of the games, either in a Mediterranean tradition of bull-leaping, or as an early form of bullfighting. Because Livy's chronology places the LudiTaurii (or in some editions Taurilia) immediately after the news of a victory in Roman Spain, the games have figured in a few efforts to trace the early history of Spanish-style bullfighting

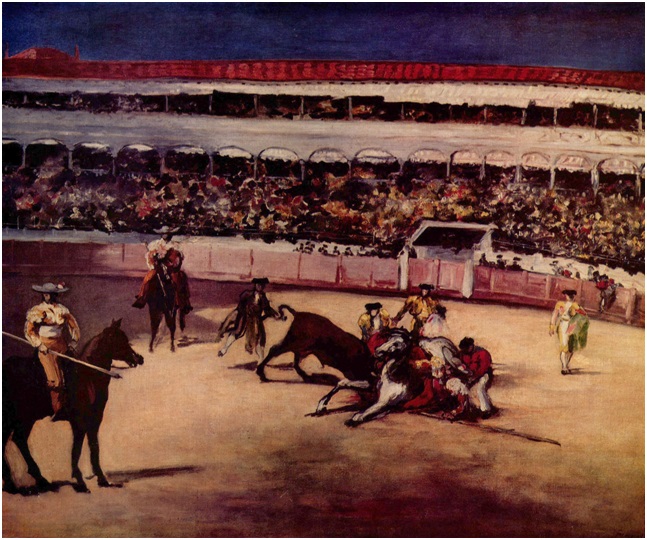

THE ORIGIN OF CORRIDA

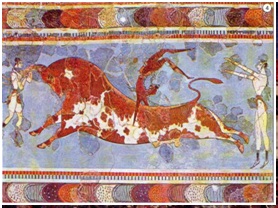

Some people want to trace the origins of bullfighting at the time of Muslim domination, while others say they were born in Greece or Rome. Testimonials of such origin are the frescoes on bullfighting Mycenaean palaces of Crete even if there are not images of killing the animal.

The relationship between the Corrida and Venationes seems much more direct , Roman games in which different animals, including the bull, were hunted and killed in circuses in ancient Rome. In addition, there are significant architectural similarities between the bullring and the Roman amphitheater of which remain even ample evidence throughout the Spanish territory. Bullfighting as we know it today, it dates back to 1500 and was practiced only by the aristocracy. The show consists of a fight between man and bull. Bullfighting ends when the matador (bullfighter) stabs the bull with a sword, killing him.

THE ROMAN THEATRE IN SPAIN

Merida Amphitheatre is a reasonably well preserved Ancient Roman amphitheatre. The Emperor Augustus (63 BC - AD 14) established the Roman colony known as Augusta Emerita - later became modern Merida - in 25 BC. Soon after its founding, Augusta Emerita became the capital of Lusitania and, as an important city of the empire, had several impressive public buildings. Merida Amphitheatre was one of these.

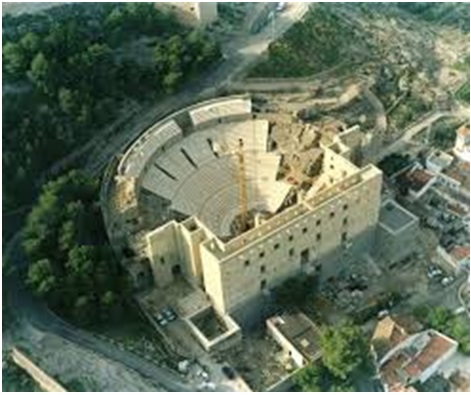

completed in 8 BC and able to seat up to 15,000 spectators, this elliptical amphitheatre was finally abandoned in the fourth century AD. Today, the walls of Merida Amphitheatre are still intact together with some of its seats and it gateways, showing a detailed outline of what it would have looked like in its day. The Roman theatre in Sagunto was built to take advantage of a depression in the land, which gives it excellent acoustics for theatrical performances staged in the open air.The theatre in Cartagena was built between 5 and 1 BC

Cartagena

Sagunto.

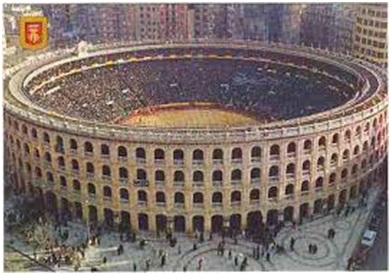

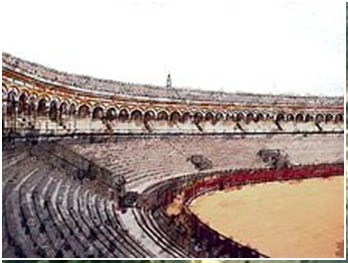

PLAZA DE TOROS

The plaza de toros (Spanish word), also known as bull or simply circus arena, originated in ancient Europe. It is an architectural structure from similar feature classical arena with different style according to the greater or lesser antiquity of the building. It is mostly a closed amphitheater of the approximately circular with bleachers and services that surround a central space where the show takes place bull. In this space thereis the ruedo or arena, which is a plot of dirt prepared in order to properly serve the show and it is surrounded by a retreat where the bullfighters take refuge and their subalterns called alley. The alley is separated from the arena by a wall, generally made of wood and about 140 centimeters in height, which has small entrances to the arena to facilitate the entry in case of emergency. It has gates for entry and exit of the participants and of the bulls, although the amount and location of these varies from fence to fence.