Multilingual people are competent in intercomprehension

Claudia Mewald, University College of Teacher Education Lower Austria

Linguistic and cultural diversity as well as migration are characteristics of our globalized world. Signs of globalization become more and more apparent and are experienced most extensively in and around metropolitan areas. Teachers are at the forefront of a rapid development of multilingualism and multiculturalism as they have to come to terms with an increasingly diverse society, its educational requirements and it multifaceted demands. Therefore, they should be aware of beneficial ways of exploiting the linguistic and cultural diversity of the learners in their classrooms and consider the targeted use of all language resources at their learners’ disposal as an important task of 21st century education. Moreover, they should acknowledge that language education is especially important for people whose linguistic resources might create barriers in their access to education or in obtaining vocational qualifications.

However, teachers cannot be left on their own with the tasks of handling increasingly heterogeneous classrooms. Methods to accelerate language learning and the effective use of shared languages as a bridge for intercomprehension, the meaning making between languages, are therefore at the heart of teaching 21st century classrooms. They are also the goal of ODIMET, a European project funded through ERASMUS+ Key Action 2.

Intercomprehension in ODIMET

When learners of diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds meet to learn together, they work in genuinely multilingual settings. So far classroom work only makes little use of the multilingual potential of the learners and avoids plurilingual tasks which consider the use of the language(s) of schooling and all the other languages at the learners’ disposal. This seems to be a waste of resources taken into consideration the benefits individual learners may have if their starting point for a task could also be an input they can comprehend fully or nearly fully while follow-up tasks in collaboration with learners who do not share their information can carry them back to the target language. Tasks which allow for more than one language in the instructions or scaffolding activities and that make use of the shared language(s) in the classroom for the output create natural information gaps that make the subsequent exchanges and the collaborative compilation of knowledge in the target language a natural process of mediation.

Therefore, ODIMET intends to draw on the potential of learners to understand a lot without understanding input completely. Children will be using authentic videos produced by their peers in new languages, multilingual learning resources and strategies not only to comprehend each other, but also to get in touch and communicate via eTwinning.

Abilities of multilingual learners and intercomprehension

Multilingual learners have acquired the ability to understand and use two or more languages. This ability may have developed equally in all skills or only in some of them. Likewise, the qualities of language ability in various skills and languages may vary. Few people are equally well equipped in all the various languages they understand or use in real life. Teachers have to be aware of this variety and acknowledge that learners who may be able to comprehend aural input may still struggle with it in its written form, particularly if they are not sufficiently familiar with the script they are expected to read or produce.

Multilingual people have also developed the ability to make sense of spoken or even written texts in and across languages they have not yet fully acquired or studied through intercomprehension. Detecting and understanding intercomprehension strategies may aid teachers in their support for learners to become more effective in their comprehension and communication. This includes the use of a Lingua Franca, this may be English as a common language, between speakers whose native languages are different.

Whenever learners use two or more languages in one conversation for the purpose of effective communication they engage in a plurilingual discourse. When they are using their acquired languages to understand the unfamiliar languages of the others and to communicate with them, they are translanguaging. This process requires intercomprehension and it works best when the learners have learnt to do this consciously.

It is a characteristic trait of intercomprehension that it does not demand the ability of verbal production in the target language. (Doyé, 2005, p. 7)

We thus differentiate between intercomprehension competence, the capacity to understand other languages without having studied them, and intercomprehensive performance during which each person uses his or her own language and understands that of the other.

In this way, intercomprehension can become an alternative or complement to the common use of a Lingua Franca. It exploits previously acquired knowledge, skills and strategies and employs extralinguistic features such as background knowledge, knowledge of the situation or visual support in making sense of languages not studied and is highly individual and dynamic in its development.

In ODIMET this will be achieved through scaffolding materials offered with each input, primarily based on visual input in videos, but also pictures, mind maps and playful educational activities.

A Framework for Intercomprehension Methodology

Teachers can foster intercomprehension in various ways. They can create learning designs that make conscious or unconscious intercomprehension possible and allow variation in the use of languages in their lessons. This can be realised in providing the opportunity for learners to draw on input in their stronger languages in addition to the input in the language of instruction or through making use of modern media and the dictionaries, glossaries, thesauruses and translation tools they offer. Teachers who allow for variation in language input, foster strategy use, support awareness for and sensitivity to language needs and who scaffold learner autonomy, establish the necessary conditions of learning (Marton, 2015) that facilitate a multilingual acquisition process. This, in turn, encourages the development of intercomprehension competence. Through establishing intercomprehension as a guiding principle, teachers in fact help pupils to “acquire the strategies needed for the understanding of the texts and utterances of any new language they might encounter in the future” (Doyé, 2005, p. 20). This can only be achieved if the various languages the learners own are given attention in the learning process and if teachers consciously employ methods that make intercomprehension explicit.

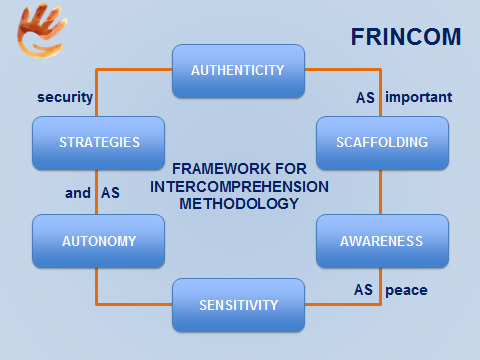

Figure 1: A Framework for Intercomprehension Methodology (Mewald,2018)

A framework for intercomprehension methodology (FRINCOM) relies on the following elements:

- authenticity of input and task (given in ODIMET through authentic videos and pen pal communication)

- scaffolding of learning task (given in ODIMET through learning activities offered with the videos)

- awareness for multilingual potential and identity (created in ODIMET through engaging in multilingual activities)

- sensitivity to cultural and personal predispositions (given in ODIMET through intercultural input and activities)

- autonomy in learning and personal language development (given in ODIMET through learning activities offered with the videos)

- strategies that foster meaning making within and across languages (given in ODIMET through playful activities offered with the videos)

The interplay of all elements is supposed to be crucial for the effectiveness of intercomprehension.

Authenticity

Children usually enter education with a reasonably sound command of their family languages and with a well-established ability to infer meaning from aural input without understanding every word they hear. Most of them will already have learnt to interpret meaning from additional clues such as body language, facial expressions, sound and tonality. The can make use of their situational knowledge and their knowledge of the world (KOW) to exploit limited language resources creatively. They mix or adapt language they have picked up when they communicate and they are inventive in creating their own languages. In most families the individual members speak different language varieties such as dialects, sociolects or idiolects, and many families even use different languages. Thus, most homes provide a plurilingual language environment and so do most playgrounds. The proximity and tetention of initial language acquisition seems to shape children’s and teenagers’ attitudes towards new languages. They create a positive, relaxed and unharmed starting point that language learning can utilize. Taylor (1994) considers the classroom a real and authentic place and other researchers support this position if skill-getting (Rivers and Temperley, 1978: 4), pre-communicative activities (Littlewood, 1992: 44) or language-learning activities are kept authentic. Breen distinguishes four types of authenticity in the language classroom. He mentions the authenticity of the texts used as input data, the authenticity of the learner’s own interpretations of such texts, the authenticity of the tasks conducive to language learning, and the authenticity of the actual social situation of the language classroom (Breen, 1985, p. 58).

Most authentic texts written by adults for children of the same age as the target group are likely to be too difficult to comprehend for beginners of a new language. Thus, teachers tend to use children’s books or materials originally produced for younger readers or listeners as well as simplified texts. In real life input is not necessarily abridged and as already mentioned, children are used to gaps in comprehension and can still make meaning from what they hear or read.

Listening to language by peers usually provides more comprehensible input because their lexical range is similar. If the input in a new language comes from peers who are native speakers of that language, this may create different challenges. However, in authentic communication the shared KOW and mutual interest in topics support successful exchanges. In this situation, strategies can also help bridge obstacles.

Strategies

When learners are asked to make meaning from texts or utterances in new languages, they usually activate prior experience and knowledge. The most intuitive strategies learners employ in this process is to search for cognates, i.e. words or phrases that are similar in meaning, pronunciation and/or spelling. In most of the cases this happens subconsciously. However, an awareness for and the strategic use of cognates in certain languages creates associations which will accelerate the comprehension of language input and the readiness to produce output. International words have similar effects on comprehension and fluency – many of them are readily available and understood. Making learners familiar with cognates and international words is therefore recommended (see Links). This seems particularly important in topic areas related to modern media and interactive computer games that include linguistic components. Similarly naturally come strategies making use of visual and additional auditory clues to understand what is going on in a text: Pictures or body language and facial expression support comprehension equally well as the conscious discernment of tonality and mood. These paralinguistic strategies draw on behavioural knowledge, i.e. the use of “verbal signs to express ideas, emotions and intentions … [and] other norms of behaviour to serve the purpose of conveying information” (Sarıçoban & Aktaş, 2011, p. 151) as well as situational experience (Doyé, 2005).

Cultural knowledge can serve or impede intercomprehension. Depending on its direction it may lead to stereotypes and false generalizations, or to shared social practice in which to participate is considered attractive. The learners’ diverse cultural knowledge and experiences are important in the development of their intercomprehension. Teachers therefore need to know about and understand their learners’ cultural backgrounds to be able to uncover the differences and similarities in their social and cultural lives and experiences. Acknowledging the cultural diversity in classrooms and knowing about cultural facts and practices can aid teaching and learning. When specific actions or events in the learners’ cultures are similar to those in the target language societies, learners will make helpful associations. If their social and personal lives differ significantly, clashes need to be bridged. Awareness for what is possible in certain cultures and sensitivity for the impossible are recommended.

In addition to intercomprehensive behaviour, which operates subconsciously, intercomprehension competence can benefit from conscious strategy use. This is the application of pragmatic knowledge about text type and its social function. Once learners have identified familiar words and gained an overall understanding of the text, they can apply selective attention to understand concrete information that is explicit and easy to identify or spot, especially if there is visual support. As soon as gist and specific information at micro level are understood, learners can be encouraged to understand detailed information in a context. This requires careful attention or reading. Depending on their readiness, learners may need different variations of scaffolding when a task requires understanding details.

Teachers, who highlight cognates and international words and who add pictures to crucial points which cannot be inferred, scaffold intercomprehension effectively.

Scaffolding and autonomy

Scaffolding and autonomy may not necessarily look like a matching pair because the former makes the learner dependent on the teacher’s or the material’s help, while the latter aims at independence in the learning process.

However, combining scaffolding and learner autonomy seems particularly important in multilingual settings. Teachers faced with a linguistically diverse group of learners cannot but personalise learning to differentiate appropriately and to cater for all learner needs. This means viewing learning as a dynamic process of knowledge creation and exploration which varies with every single learner (Herdina & Jessner, 2000). Making learning meaningful for a linguistically and culturally diverse group of learners goes beyond identifying topics of interest. Fostering intercomprehension requires teachers to provide scaffolds so that every single learner can make their own connections and develop a personal understanding of what they are expected to learn. This includes a careful analysis of what individual learners already know and to provide them with the necessary scaffolds to understand and learn based on the information gained. Teachers cannot possibly do this simultaneously for a whole class. Therefore, materials and tasks with opportunities for self- and peer-assessment are necessary scaffolds in heterogeneous settings.

Intercomprehension works best when learners have opportunities to reflect on what they understand, how they understand it and what they need to do next to understand more. Teachers therefore need to employ varied approaches and materials that allow for different ways how learners approach text and how they make meaning from them. This may include variation in input, which can be written or aural, supported by visuals or subtext in a Lingua Franca all learners in the group understand – in most cases this is ELF. This may also include input in the strongest language when prior contextual and content understanding may aid comprehension in the new language. Planning intercomprehension can thus never be seen as a finished process resulting in a lesson plan that will be followed strictly. Effective planning for intercomprehension is a dialogic and dynamic process in which goals, activities and materials are varied according to learners’ reactions and needs. What looks like a messy process is in reality an interactionalist approach based on a resourceful programme that fosters learner autonomy including diagnostic material with a component of immediate feedback that enables teachers to

- select learning objectives that relate to the individual learner,

- identify suitable learning material and scaffold their implementation,

- observe learner behaviour, assess their performance and/or encourage self- and/or peer-assessment, and to

- select new objectives and materials based on previous learning outcomes.

Learners who are developing self-direction in such learning scenarios should be able to rely on mutual understanding and support. Thus, they will learn to readjust and select simpler or more challenging material according to informed decisions based on evidence of successful or failed comprehension.

The following scaffolds are considered useful in intercomprehension methodology:

- visualisation

- annotated input texts (margin notes, word banks, glossaries…)

- digital texts with the opportunity to use on-line dictionaries and thesauruses

- video input subtitled in the target language, the shared Lingua Franca or the individual learner’s strongest language with the opportunity for repeated input

- highlighted texts with margin notes and summaries

- glossaries

Awareness and sensitivity

Making learners aware of their competences and what they can do in their various languages is motivating. Encouraging them to make use of all their resources available to make sense of new texts, taps into concepts of strategies as well as autonomy. The super-teacher who is able to detect all connections their learners are making at a certain moment does not exist. It lies in the learners themselves, to become aware and sensitive to learning opportunities and meaningful connections between their languages.

Nevertheless, it is the teacher’s task to convey that intercultural communication is mutually compassionate, respectful, tolerant and collaborative. Teachers should be aiming at transcultural education which differs from intercultural education in that it intends to create a transformed cultural understanding and shared new cultures rather than parallel worlds of two or more cultures next to each other.

AS important AS peace and AS security

The elements of FRINCOM can be abbreviated in its three “As” and the mnemonic aid they create refer to the overarching goal of the project that intends to develop this methodology: AS important AS peace and AS security. Security is important in any learning process. Security can be provided if learners know where they are going, how they will get there and what they can do if they get lost on their way. The “where” is given by defined goals, the “how” is demonstrated through the implementation of strategies and “what” to do in case of disorientation is determined by the scaffolding the teachers provide or the learners select. The more autonomous learners are in their selection, the faster they will obtain the necessary help. This, however, requires targeted diagnosis and feedback, because

… any teaching method is most useful when there is plenty of prompt feedback about whether the student is thinking about a problem in the right way. (Hattie, 2012, p. 88)

Speed in the delivery of feedback is crucial for its effectiveness. Therefore, self-directed and collaborative solutions like self- and peer-assessment should be encouraged. This closes the circle to awareness and sensitivity. These elements are crucial in the process of developing intercomprehension. In the absence of awareness all the other elements can be applied, but they will not succeed in creating an understanding between languages. Sensitivity on the other hand is equally important, especially in the provision of feedback. Last but not least, authenticity needs to be mentioned as the overarching element which transcends all the other elements in that any work in language education that does not create an authentic need for communication or that does not aim for an authentic use will not trigger the kind of comprehension that it takes to make learners create meaning through and within all the linguistic resources they possess.

Peace - at last

This contribution started with the claim that linguistic and cultural diversity as well as migration are prominent characteristics of our globalized environment. I would like to end it with the hope that sufficient und successful intercomprehension supports the awareness that a globalized and peaceful world depends on

... people who can communicate, each speaking his own language and understanding that of the other, but who, while not being able to speak it fluently, by understanding it, even with difficulty, would understand the “spirit”, the cultural universe that everyone expresses when speaking the language of his ancestors and of his own tradition. (Eco, 1994, p. 292)

Therefore, the project ODIMET also supports citizenship education.

Bibliography

Breen, M. P., 1985. Authenticity in the Language Classroom. Applied Linguistics,, Volume 6(1), pp. 60-70.

Doyé, P., 2005. Intercomprehension. Guide for the development of language education policies in Europe: from linguistic diversity to plurilingual education. Reference study. [Online]

Available at: https://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Doye%20EN.pdf

Eco, U., 1994. The Limits of Interpretation. Bloomington: ndiana University Press.

Emberley, E., 1992. Go Away Big Green Monster!. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

Hattie, J., 2012. Visible Learning for Teachers. Maximising Impact on Learning. New York: Routledge.

Herdina, P. & Jessner, U., 2000. A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism: Changing the Psycholinguistic Prespective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Marton, F., 2015. Necessary Conditions of Learning. New York: Routledge.

Sarıçoban, A. & Aktaş, D., 2011. A New Intercomprehension Model: Reservoir Model. The Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 7(2), pp. 144-163.

Mewald, C. (2018) Framing a Methodology for Intercomprehension. R&E-SOURCE , INTERNATIONAL WEEK 2018 - ERASMUS+ PROJECT PALM /PALM Symposium. Available at: https://journal.ph-noe.ac.at/index.php/resource/article/view/589

Taylor, D., 1994. TESL-EJ: Inauthentic Authenticity or Authentic Inauthenticity?. The Electronic Journal for English as a Second Language, 1(2).

Links

English Cognate Words understandable to Spanish, Portuguese, French and Italian speakers http://www.cognates.org/pdf/cognated-oklahoma-academic-vocabulary.pdf

Cognates in the Cambridge P.E.T. (Preliminary English Test) Vocabulary List – CEFR B1

http://www.cognates.org/pdf/cognated-cambridge-preliminary-vocab.pdf

Basic International Wordlist

https://simple.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Basic_English_international_wordlist

Ogden’s International Word List

http://ogden.basic-english.org/intlword.html

International Internet Words

http://www.basic-english.org/21/internet.html

21st century basic English International Words

http://www.basic-english.org/21/intword.html

Foreign words and phrases in English

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/explore/foreign-words-and-phrases

Tutorials for teachers to create playful language learning activities and lexical notebooks

…. can be found on the Website PALM — please register as a teacher!

https://www.palm-edu.eu/en/palm4teachers/tutorials/